Miller and evans anatomy of the dog, 5th edition

Bạn đang xem bản rút gọn của tài liệu. Xem và tải ngay bản đầy đủ của tài liệu tại đây (42.25 MB, 2,119 trang )

Miller and Evans'

Anatomy of the Dog

FIFTH EDITION

John W. Hermanson, PhD

Associate Professor

Department of Biomedical Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York

Alexander de Lahunta, DVM, PhD

James Law Professor of Anatomy, Emeritus

Department of Biomedical Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York

Howard E. Evans, PhD

Professor of Veterinary and Comparative Anatomy, Emeritus

Department of Biomedical Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York

2

www.pdfgrip.com

3

www.pdfgrip.com

Table of Contents

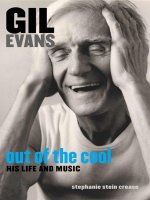

Cover image

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Special Dedication

About the Authors

Preface

Anatomical Terms

Planes of the Body

Movement

Literature

Acknowledgments

Contributors

Former Contributors in Past Editions

1 The Dog and Its Relatives

The Order Carnivora

4

www.pdfgrip.com

The Family Canidae

Breeds of Dogs

Bibliography

2 Prenatal Development

Early Development

Length of Gestation

Prenatal Periods

Oocyte–Embryo

Embryo

Age Determination

Fetus

Bibliography

3 The Integument

Epidermis

Dermis

Structure of the Dermis and Changes with Age

Pigmentation

Nasal Skin

Digital Pads

Hairy Skin

Muscles of the Skin

Glands of the Skin

Blood Supply to the Skin

Nerve Supply to the Skin

Skin Grafting

Claw

5

www.pdfgrip.com

Bibliography

4 The Skeleton

General

Axial Skeleton

Appendicular Skeleton

Bibliography

5 Arthrology

General

Ligaments and Joints of the Skull

Ligaments and Joints of the Vertebral Column

Ligaments and Joints of the Ribs and Sternum

Ligaments and Joints of the Thoracic Limb

Ligaments and Joints of the Pelvic Limb

Bibliography

6 The Muscular System

Introduction

Skeletal Muscles

Muscle Description

Muscles of the Head

Muscles of the Neck

Muscles of the Dorsum

Muscles of the Thoracic Wall (Musculi Thoracis)

Muscles of the Abdominal Wall (Musculi Abdominis)

Muscles of the Tail (Musculi Caudae)

Fasciae of the Trunk and Tail

Muscles of the Thoracic Limb

6

www.pdfgrip.com

Muscles of the Pelvic Limb

Bibliography

7 The Digestive Apparatus and Abdomen

Oral Cavity

Pharynx

The Alimentary Canal

Liver

Pancreas

Bibliography

8 The Respiratory System

External Nose

Nasal Cavity

Larynx

Trachea

Bronchi

Thoracic Cavity and Pleurae

Lungs

Bibliography

9 The Urogenital System

Urinary Organs

Reproductive Organs

Embryologic Characteristics of the Urogenital System

Bibliography

10 The Endocrine System

General Features of the Endocrine Glands

7

www.pdfgrip.com

The Hypophysis

Thyroid Gland

Parathyroid Glands

Pineal Gland

Adrenal Gland

Pars Endocrina Pancreatis

Enteroendocrine Cells

Endocrine Tissues of the Ovary

Fetal Membrane Endocrine Tissues

Endocrine Tissues of the Testis

Endocrine Cells of the Kidney

Bibliography

11 The Heart and Arteries

Pericardium and Heart

Pulmonary Arteries and Veins

Systemic Arteries

Bibliography

12 The Veins

General Considerations

Cranial Vena Cava

Veins of the Thoracic Limb

Caudal Vena Cava

Portal Vein

Veins of the Pelvic Limb

Veins of the Central Nervous System

Bibliography

8

www.pdfgrip.com

13 The Lymphatic System

General Considerations

Ontogenesis of the Lymphatic System

Lymph Drainage

Lymph Vessels

Innervation of Lymph Vessels and Lymph Nodes

Lymphoid Tissue

Lymph Nodes

Hemal Nodes

Lymph Nodules

Regional Anatomy of the Lymphatic System

Bibliography

14 Introduction to the Nervous System

General

Functional Components of Nerves

Reflexes

Bibliography

15 The Autonomic Nervous System

General Visceral Efferent System

Enteric Nervous System

Bibliography

16 The Spinal Cord and Meninges

The Spinal Cord

Morphologic Features of the Spinal Cord

Spinal Cord Segments

9

www.pdfgrip.com

Segmental Relationships to Vertebrae

Gray Matter of the Spinal Cord

White Matter of the Spinal Cord

Spinal Reflexes

Transverse Sections of the Spinal Cord

Meninges, Brain Ventricles, and Cerebrospinal Fluid

Bibliography

17 The Spinal Nerves

Initial or Primary Branches of a Typical Spinal Nerve

General Features of Spinal Nerves

Cervical Nerves

Nerves to the Diaphragm

Brachial Plexus

Thoracic Nerves

Lumbar Nerves

Sacral Nerves

Caudal Nerves

Bibliography

18 The Brain

The Brainstem

The Subthalamus

The Cerebrum

Basal Nuclei

The Cerebellum

Brain Atlas

Bibliography

10

www.pdfgrip.com

19 Cranial Nerves

Olfactory Nerve (Cranial Nerve I)

Optic Nerve (Cranial Nerve II)

Oculomotor Nerve (Cranial Nerve III)

Trochlear Nerve (Cranial Nerve IV)

Trigeminal Nerve (Cranial Nerve V)

Abducent Nerve (Cranial Nerve VI)

Facial Nerve (Cranial Nerve VII)

Vestibulocochlear Nerve (Cranial Nerve VIII)

Glossopharyngeal Nerve (Cranial Nerve IX)

Vagus Nerve (Cranial Nerve X)

Accessory Nerve (Cranial Nerve XI)

Hypoglossal Nerve (Cranial Nerve XII)

Cutaneous Innervation of the Head by Noncranial Nerves

Bibliography

20 The Ear

The Internal Ear

The Middle Ear

The External Ear

Bibliography

21 The Eye

Development

The Eyeball

The Eye as an Optical Device

Orbit

Eyelids

11

www.pdfgrip.com

Lacrimal Apparatus

Muscles

Innervation

Vasculature

Comparative Ophthalmology

Bibliography

Index

12

www.pdfgrip.com

Copyright

3251 Riverport Lane

St. Louis, Missouri 63043

MILLER AND EVANS' ANATOMY OF THE DOG, FIFTH EDITION ISBN: 9780-323-54601-0

Copyright © 2020, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Previous editions copyrighted 2013, 1993, 1979 and 1964.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the

publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the

Publisher's permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as

the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found

at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under

copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein).

Notices

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and

knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or

experiments described herein. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences,

in particular, independent verification of diagnoses and drug dosages should be

made. To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors,

contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to

persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or

from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas

contained in the material herein.

978-0-323-54601-0

13

www.pdfgrip.com

Content Strategist: Jennifer Flynn-Briggs

Content Development Management: Ellen Wurm-Cutter

Content Development Specialist: Melissa Rawe

Publishing Services Manager: Shereen Jameel

Project Manager: Aparna Venkatachalam

Designer: Ryan Cook

Printed in China

Last digit is the print number: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

14

www.pdfgrip.com

Dedication

Sandy de Lahunta and Howard Evans collectively were on the anatomy faculty

from 1950 to 2005 at Cornell University. This represents a remarkable span of

time during which they mentored a multitude of students and worked together as

colleagues. With this fifth edition, we recognize the contribution of Professor Evans

in the title: Miller and Evans' Anatomy of the Dog.

Cornell Graduation, 2005

15

www.pdfgrip.com

Special Dedication

Malcolm E. Miller, BS, DVM, MS, PhD (1909–1960). Dr. Malcolm E. Miller

was born on a farm in Durrell, Pennsylvania; studied for two years at

Pennsylvania State University; and then earned his BS and DVM (1934), MS

(1936), and PhD (1940) degrees from Cornell University. He was appointed

Instructor in 1935 and, at the time of his death, was Professor and Head of

the Department of Anatomy and Secretary of the New York State

Veterinary College at Cornell University. His zest for life, devotion to his

family, and his enjoyment of teaching and anatomical research sustained

his spirit through several brain operations which provided only temporary

relief from epileptic attacks.

This volume was envisioned by Dr. Miller in 1944 as a comprehensive

treatise documenting the morphology of the dog. His efforts were aided

considerably by the encouragement of Dean W.A. Hagan and the

appointment of a medical illustrator in 1946. Preliminary work with the

16

www.pdfgrip.com

help of his wife, Mary, resulted in the 1947 publication by Edwards

Brothers Press of Miller's Guide to the Dissection of the Dog, which now

appears as Guide to the Dissection of the Dog, eighth edition (2017) by Evans

and de Lahunta.

17

www.pdfgrip.com

About the Authors

Howard Evans was an undergraduate student in Entomology at Cornell University

when he was called to active duty in the Army during World War II in 1943. Upon

completion of 3 years of service as a Second Lieutenant and graduation from Cornell

in absentia, he returned as a graduate teaching assistant in Comparative Anatomy.

He received a PhD in 1950, with a thesis on the anatomy of Cyprinid fishes. That

same year he was hired by Dr. Malcolm Miller as an Assistant Professor in the

Veterinary College. He taught Veterinary Anatomy for 36 years until his retirement

in 1986. During his tenure, he taught Dog Anatomy, Horse and Cow Anatomy, and

the Anatomy of Fish and Birds. As an emeritus professor, he has taught a course on

Natural History to veterinary students at Cornell for 12 years. For 2 or 3 weeks each

year since 2002, he has taught Fish and Bird Anatomy and Natural History at St.

George's University Veterinary College in Grenada, West Indies.

He was a co-author of the first and second editions of Miller's Anatomy of the Dog

and the sole author of the third edition. The fourth edition with Dr. de Lahunta was

the first to have all illustrations in color. He is co-author with Dr. de Lahunta of

Guide to the Dissection of the Dog, which is in its eighth edition. Evans has written

chapters in other texts on tropical fish anatomy, bird anatomy, ferret anatomy, and

woodchuck anatomy. His research has concerned fetal development of Beagle dogs,

cyclopia in sheep, and the replacement of teeth in fishes. His sabbaticals were spent

at the Veterinary College in Davis, California, learning surgical techniques for fetal

studies of dog development; the University of Hawaii, teaching Comparative

Anatomy; the Medical School of the University of Pennsylvania, studying fetal

development of sheep; and the Marine Station of the University of Georgia, studying

the anatomy of the Spotted Sea trout.

His interest in natural history led to giving courses to veterinary students at

Cornell and at St. George's University in Grenada, West Indies. He and his wife Erica

have led many Cornell University trips to Africa, Hawaii, New Guinea, and

Antarctica. He has continued to enjoy his interactions with students and sharing the

anatomical collections in his office almost daily since his retirement in 1986.

Alexander de Lahunta (“Sandy” to his colleagues, or “Dr. D.” as he was known to

his students) received his DVM from the College of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell

18

www.pdfgrip.com

University in 1958. After 2 years of mixed practice in Concord, New Hampshire, he

returned to the Department of Anatomy at Cornell where he obtained his PhD. For

the next 42 years he taught gross anatomy of the dog, veterinary neuroanatomy and

clinical neurology, applied anatomy, embryology, and neuropathology.

He established a consultation service in clinical neurology in the Teaching

Hospital and was a founding member of the Neurology Specialty of the American

College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM).

He was chairperson of the newly developed Department of Clinical Sciences. He

received numerous awards for his teaching and the Robert W. Kirk Distinguished

Service Award of the ACVIM. He retired in 2005 and has been active in textbook

writing since that time.

In addition to this text, he has authored or co-authored a fourth edition of

Veterinary Neuroanatomy and Clinical Neurology, an eighth edition of Miller's Guide to

the Dissection of the Dog, The Embryology of Domestic Animals: Developmental

Mechanisms and Malformations, Veterinary Neuropathology, and Applied Anatomy.

John Hermanson was an undergraduate at the University of Massachusetts,

Amherst, where he first became interested in comparative vertebrate anatomy as a

student of the late David Klingener. He received an MS from Northern Arizona

University in 1978, and a PhD from the University of Florida in 1983. It was at

Florida where he first engaged in teaching veterinary anatomy at the College of

Veterinary Medicine in Gainesville. After postdoctoral studies at Emory University

(neuroscience) and at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (muscle

regeneration), he began his career at Cornell University in 1987. He has taught

anatomy of “whatever is in the barnyard” since that time, including Horse Anatomy,

Ruminant Anatomy, Bird Anatomy, and comparative anatomy that caters to lab

animal, zoo animal, and wildlife conservation interests. His research has spanned bat

biology, equine biomechanics, and paleontology.

19

www.pdfgrip.com

Preface

The first edition of this text was based on an unfinished manuscript with

illustrations that Professor Miller had been working on for many years prior to his

death in 1960. At the request of his wife, Mary Miller (Ewing), the manuscript was

completed by Howard E. Evans and George C. Christensen. The first edition of

Anatomy of the Dog by Miller, Christensen, and Evans appeared in 1964. “Mac” Miller

had supervised the preparation and completion of almost all of the illustrations by

Pat Barrow and Marion Newson that appeared in the first edition.

The second edition, entitled Miller's Anatomy of the Dog, by Evans and Christensen,

was published in 1979. It incorporated the most recent nomenclature of Nomina

Anatomica Veterinaria and had new chapters on fetal development, the endocrine

system, the spinal cord, and the eye. There were also many new drawings by Marion

Newson, Lewis Sadler, and William Hamilton.

The third edition of Miller's Anatomy of the Dog, by Evans, updated the literature,

added new material, and incorporated nomenclatorial changes that appeared in

Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria 1983. Many figures were modified structurally or

relabeled, and several were replaced. There were chapters by eight new contributors,

and the introductory chapter was expanded to include the phylogenetic

relationships of canids to other carnivores and the history of domestication of the

dog. The chapter on muscles was augmented to include current histochemical and

electrophysiologic evidence of muscle function. The material on the nervous system

was amplified by new chapters on the brain and cranial nerves.

Miller's Anatomy of the Dog attempts to meet the varied needs of anatomists,

veterinary students, clinicians, and experimentalists. Throughout the text, the intent

is to describe and illustrate the specific morphology of the dog, with reference to

older literature. Although there are many similarities between species, it is often

surprising how different anatomical specifics can be. What is a functional structure

in one may be only a vestige or absent in another, and care is required when

extrapolating to other species.

The fourth edition was the first fully colorized version, and it required removal of

all former labels (which were made with LeRoy lettering stencils, something

unknown to new generations of students) and dotted lead-lines. Some of these

illustrations appeared in the eighth edition of Guide to the Dissection of the Dog (2017,

20

www.pdfgrip.com

Elsevier/Saunders) by Evans and de Lahunta.

This fifth edition includes many new radiographs and computed tomography (CT)

scans that were kindly provided by Dr. Peter Scrivani, supplementing a number of

radiographs from earlier editions that were contributed by Dr. Vic Rendano. New

digital imaging technology allows an ever-improving insight into the structure of the

dog's body. Michael Simmons provided new illustrative interpretations of a number

of images of the lymphatic system, replacing images that had grown darker with

each subsequent printing. Illustrations were added or updated in Chapter 21.

Nomenclatural revisions were included as appropriate, and we attempted to retain

some synonyms where their use would clarify discrepancies with human medical

anatomy texts and other veterinary anatomy texts. New research was referenced

throughout the text to enhance our interpretations of anatomic structures.

We appreciated correspondence received and offer our thanks to the many people

who pointed out errors or suggested improvements. The illustrations have been

particularly well received, and requests for their reuse in books and journals stand as

a tribute to the dissectors and illustrators whose combined efforts produced them.

Anatomical Terms

The terms used for structures of the body are numerous, and, in the course of

medical history, about 50,000 names have been given to some 5000 structures. This

has led to considerable ambiguity.

The history of anatomical terminology shows gradual regional changes from the

Arabic to the Greek of Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen to the Latin of Vesalius,

Fallopius, Eustachius, Fabricius, and Malphighi, when the center of medical

education shifted to Italy. Some Arabic terms, such as “saphena” and “nucha,”

remain, as do several Greek terms, some with Latin endings. Each country often

used different endings for Latin terms, and later vernacular terms made the medical

vocabulary unusable internationally. (For example, the hypophysis, or pituitary

gland, had at least 30 names in Greek, Latin, German, French, and English.)

For any meaningful communication, it is necessary that anatomical terms be clear

and precise. With this in mind, international anatomical nomenclature committees

sponsored by various anatomical societies have published Nomina for humans

(Nomina Anatomica [NA], 1989 and Terminologia Anatomica [TA], 1998), and Nomina

for domestic animals (Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria [NAV], 2005), and (Nomina

Anatomica Avium [NAA], 1993) to promote international communication and

facilitate learning. There are lists of Nomina for gross, histologic, and embryologic

terms.

Several anatomists, including Burt Green Wilder, MD, Professor of Physiology,

Vertebrate Zoology, and Neurology at Cornell and Secretary of the Committee on

Anatomical Nomenclature of the Association of American Anatomists, tried

(between 1880 and 1890) to standardize anatomical nomenclature, but their results

21

www.pdfgrip.com

lacked international agreement. In 1887, the German Anatomical Society undertook

the task and assembled an international committee that worked for 6 years before

issuing a final list in 1895. This Basel Nomina Anatomica (BNA) for the human

included about 5000 terms from approximately 30,000 proposed by the

subcommittee (O'Rahilly, 1989, “Anatomical terminology, then and now.” Acta Anat.

134:291–300). This BNA formed the basis for subsequent revisions in Birmingham

(BR) in 1933, Jena (JNA) in 1936, and Paris in 1955. The latter was published as the

first edition of the NA. In 1977, the fourth edition of the NA included Nomina

Histologica (NH) and Nomina Embryologica (NE). The current NA for the human is in

its sixth edition. In 1989, the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists

created a new committee to write Terminologica Anatomica (TA), which was

published in 1998 by Thieme. Both the NA and the TA are only for human anatomy.

A committee on veterinary anatomical nomenclature was established in 1895, at

the Sixth International Veterinary Congress in Bern because the BNA was not

applicable to domestic animals. At the next Veterinary Congress in Baden-Baden in

1899, a nomenclature for domestic animals was approved but not printed or

distributed internationally, although the terms were used in several textbooks. In

1923, the American Veterinary Medical Association published the Nomina Anatomica

Veterinaria (NAV) based on the BNA, but it was not widely known or used. In 1957,

the International Association of Veterinary Anatomists established a nomenclature

committee that incorporated the earlier unpublished lists of the American

Association of Veterinary Anatomists with terms in current use. After several

preliminary lists and many meetings in different countries, the first edition of the

internationally approved NAV was published by the World Association of

Veterinary Anatomists in 1968. This Nomina is currently in a sixth edition (2017) and

is available for free on the worldwide web.

Although anatomical structures are quite stable, our understanding and

interpretation of what we see will continue to require changes at all levels: gross,

microscopic, and ultrastructural. Formal procedures exist for making changes in

anatomical terms, and the International Committee for Veterinary Anatomical

Nomenclature of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists welcomes

suggestions and help.

The terminology used in this text follows NAV 2005, with subsequent

recommendations (NAV 2017). We also consulted Constantinescu and Schaller's

Illustrated Veterinary Anatomical Nomenclature (2012) as we considered terminology

used in this edition. The following constraints serve as guidelines in the work of

anatomical nomenclature committees:

1. Each anatomical concept should be designated by a single term. Synonyms

have been used in rare exceptions, usually as transitional terms, but in some

cases both terms may be used such as: peroneus = fibularis.

2. Each term should be in Latin (Greek remains in some terms: ischiadic [G.] =

22

www.pdfgrip.com

sciatic [L.]; splen [G.] = lien [L.]).

3. Each term should be as short and simple as possible.

4. The terms should be easy to remember and should have instructive and

descriptive value.

5. Structures that are closely related topographically should have similar

names (e.g., femur: femoral artery, vein, and nerve).

6. Differentiating adjectives should generally be opposites (major/minor;

superficial/deep).

7. Terms derived from proper names (eponyms) should not be used because

the choice of the eponym has varied by country and was not descriptive of

the structure (e.g., Eustachian tube = auditory tube; canal of Schlemm =

scleral venous sinus; foramen of Monro = interventricular foramen).

Directional terms as applied to quadrupeds are different from those applied to

humans. The anatomical position of a standing dog is with four paws on the

supporting surface and the abdomen ventral. For a human, the standing position is

with the forelimbs hanging by the side, palms held forward: the palms and the

abdomen are thus considered to be anterior. For the dog, the terms cranial and caudal

apply to the neck, trunk, and tail as well as to the limbs as far distally as the end of

the antebrachium and crus. The terms for the forepaw or manus are dorsal and

palmar; those for the hindpaw or pes are dorsal and plantar. On the head the terms

rostral, caudal, dorsal, and ventral are preferred. Only in a few locations, such as the

jaws, eye, and inner ear, are such terms as anterior, posterior, superior, and inferior

used. Medialis and lateralis apply to the whole body except on the digits, where axialis

and abaxialis refer to the sides of the digit toward the axis of the limb or away from

the axis of the limb, respectively. The axis of the limb passes between the third and

the fourth digits.

Planes of the Body

The planes of the body are formed by any two points that can be connected by a

straight line.

Median Plane: Divides the head, body, or limb longitudinally into equal right

and left halves.

Sagittal Plane: Passes through the head, body, or limb parallel to the median

plane.

Transverse Plane: Cuts across the head, body, or limb at a right angle to its

long axis or across the long axis of an organ or a part.

Dorsal Plane: Runs at right angles to the median and transverse planes and

divides the body or head into dorsal and ventral portions (see Fig. PF1.1).

23

www.pdfgrip.com

FIG. PF1.1 (From Guide to the Dissection of the Dog, by Evans and de Lahunta,

Elsevier, 2017.)

Movement

Parts of the body can move relative to one another primarily because of muscular

action on bones articulated with each other by joints. Flexion is the movement of one

bone on another so that the angle between them is reduced; thus, the limb, digit, or

vertebral column is bent, folded, retracted, or arched. Extension is the lengthening of

a part by increasing the angle between bones, straightening the limb, digit, or

vertebral column. Extension beyond 180 degrees is overextension (sometimes referred

to as dorsiflexion).

Abduction is the moving of a part away from the median plane; adduction is the

moving of a part toward the median plane. Rotation is the movement of a part

around its long axis (action of the radius when using a screwdriver). Supination

(lying on the back = supine) is lateral rotation of the paw so that the palmar or

plantar surface faces medially or dorsally. Pronation (lying on the belly = prone) is

medial rotation so that the palmar or plantar surface of the paw faces ventrally.

On radiographs the view is described in relation to the direction of penetration by

the x-ray: from the point of entrance to the point of exit before striking the film. A

radiograph of the carpus in the standing position with the film under the palmar

surface of the paw would be a dorsopalmar view.

In the text that follows, structures are generally designated by their anglicized

terms in common use unless none exists. Each term, when introduced for the first

time, is followed by its Latin equivalent.

24

www.pdfgrip.com

Literature

Much anatomical information is published in several thousand scientific journals, of

which about 100 frequently contain anatomical articles in one of several languages.

Language differences and the accessibility of periodicals are still considerable

barriers to the dissemination of anatomical information, although abstracting

services and electronic retrieval systems have eased the burden of keeping current.

Literature on anatomy of the dog is not always easy to categorize by system, and,

as a result, there are many old as well as recent monographs and books that are not

cited by abstracting systems or in the chapters that follow. Some are little known: for

example, the extensively illustrated doctoral thesis of Madeleine A. Hamon “Atlas

de la Tete du Chien: Coupes Series-Radioanatomie-Tomographies” (1977) presented

at the University Paul Sabatier of Toulouse. This study includes serial transverse,

sagittal, and horizontal sections and has a bibliography of 997 references relating to

structures of the head of the dog. Current interest in multiplanar imaging, such as

CT scans, ultrasonography (sonograms), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

scans make such works invaluable. A book that compares body sections of the dog

with scans is the Atlas of Correlative Imaging Anatomy of the Normal Dog: Ultrasound

and Computed Tomography, by Feeney, Fletcher, and Hardy (Saunders, 1991). For

radiographic anatomy, the most detailed source is the Atlas of Radiographic Anatomy

of the Dog and Cat, by Schebitz, Wilkens, and Waibl (Elsevier, 2011). Thrall's recently

published seventh edition of Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology (Saunders,

2018) is also highly useful.

Dated but still useful and authoritative anatomical information on the dog can be

found in the out-of-print Handbuch der Vergleichenden Anatomie der Haustiere, by

Ellenberger and Baum (1943). Dissection guides for the dog include Atlas der

Anatomie des Hundes, by Budras (Hannover: Schluter, 2010); Canine Anatomy: A

Systemic Study, by Adams (Ames, Iowa State University Press, 2004); Dog and Cat

Dissection Guide, by Susan and Chris Pasquini (Pilot Point Texas, 2009); A Regional

Approach to the Dissection of the Dog by M.S.A. Kumar (Linus Learning, 2017); and

Guide to the Dissection of the Dog, by Evans and de Lahunta (Elsevier 2017).

25

www.pdfgrip.com